Progress Through Simplicity: On Human Progress and the History of Logic

by Cesare Cherchi

December 2025 – We argue against the notion that human knowledge necessarily grows more complex in time. Instead, I propose that significant intellectual progress, particularly in mathematics and logic, arises from simplification and the creation of new conceptual tools and abstractions, making complex problems more accessible. Using examples taken from the history of logic, physics and mathematics we show how human progress is not just about tackling complexity, but crucially about reconceptualizing problems and developing simpler, more effective frameworks. We finally suggest that a lack of simplicity, rather than complexity, might often be the true impediment to intellectual advancement.

About Cesare Cerchi

Cesare Cherchi (Macerata, 1997) teaches logic and its whereabouts at Charles university in Prague, where is pursuing his PhD with a project on doxastic logics. Among his interest there are history of logic, modal logic and metaphysics.

Bourbaki, Difficult Proofs and Easy Exercises

In the eighth volume of Nicolas Bourbaki’s Elements of Mathematics, which is dedicated to algebra, there is an exercise: exercise 1 of chapter V, to be precise. The exercise asks the following: prove that the set of numbers transcendental over Q has the cardinality of the continuum. For most people, the formulation itself will be quite mysterious and will require some explanation. Numbers come in different kinds, with natural numbers being our usual 0, 1, 2, 3… and so on to infinity, and we call their set ℕ. However, natural numbers are not all the numbers there are. For example, a natural number divided by another is not necessarily a natural number itself: 45/7 equals 5, but 44/7 does not equal any natural number. We say that 44/7 is a rational number — that is, a number that can be expressed as the ratio of two natural numbers.

The set of rational numbers is called ℚ, and ℚ is also infinite, but again, not all numbers are rational; for example, the square root of 2, which famously cannot be written as any fraction of naturals, is not rational. However, it can be expressed by an algebraic equation: in x²-2=0, x is equal to √2. We call numbers like this “algebraic” and will indicate them here with ℚ*. Finally, there are numbers that are not even algebraic; π is one of these, and we call these transcendental numbers, which form part of the set of real numbers ℝ, which is the set of almost all the numbers there are. Our sets of numbers include each other concentrically. Going from “larger” to “smaller,” we have ℝ⊂ℚ*⊂ℚ⊂ℕ, where ⊂ comes from the ‘c’ of ‘contains.’

The exercise asks us to prove something very specific about the cardinality of the numbers transcendent on ℚ; that is, the numbers in ℝ that are not in ℚ*. Specifically, it asks us to prove that the cardinality of ℝ-ℚ* (where ‘-’ denotes difference) is equal to the cardinality of ℝ. Regarding cardinality, the cardinality of a set is simply its size. For example, a set of random objects, S={x, y, z}, has cardinality 3 and is smaller than the set R={a, b, c, d} which has a cardinality of 4. This is easy to see: no matter how I pair the objects of S with the ones of R, I will be left with an extra object from R. So we can say that R>S. This is what cardinality is, a nice and intuitive concept, but with infinite set for instance the thing is quite different: let’s imagine the case of the set of all odd numbers, what is their cardinality? Intuitively we could say that it is exactly half as natural numbers’, after all for any selection of consecutive natural numbers we find that odd numbers always constitute approximately half of the selection. However, if we try to use the same method as before to determine the bigger set we find something strange, that is, taken {1, 2, 3…} and {1, 3, 5…} we realize that they can in fact be arranged in a one-to-one correspondence, as in (1, 1), (2, 3), (3, 5)… and we will never run out of odd numbers, so there are as many odd numbers as there are natural numbers. Infinite sets are not intuitive.

This equinumerosity is not always trivial, for instance if we try to associate natural numbers with real numbers things gets tricky. Let’s define a real number as any number written any, possibly infinite, string of digits. We start to pair our numbers in order, on one side we take 1 and on the other… on the other which number do we choose? We would like to start from the smallest, but what is the smallest real number? It would be something like 0.0000000… with a 1 at the end somewhere, but for any number of this kind is easy to come up with a smaller one, it suffice to add another zero to the sequence. So, it appears we cannot pair our numbers in order and, in fact, we cannot pair them at all. In short some infinities are bigger then other and we have to work out whether is the case every time, the exercise is just an instance of the kind. Which is bigger between ℝ-ℚ* and ℝ?

The fact is that what the exercise ask us to prove is actually a theorem of great importance, proved by Georg Cantor in 1897. How is it possible that by 1942, the year Bourbaki’s Algebra came out, it was an exercise one could trust a master student to solve? Is it that the students of today (and then) are so much more intelligent than the mathematicians a couple generation their senior?

The Nature of Progress

Many discourses about progress implicitly presuppose the idea that human knowledge becomes progressively more difficult to understand over time, although this is rarely explicitly stated. After all, it seems evident that, the more we discover about the world, the more difficult the concepts required to understand it become. This idea has two time-symmetric consequences: on the one hand, it leads us to assume that any intellectual activity in the past was easier per se (i.e. without considering external factors such as culture and society). On average, any field would have required less time to master, and any concept would have taken less time to learn. Conversely, we might reach a point where we run out of things to discover, not because we have discovered everything there is to know, but because our minds cannot progress any further. Eventually, we will be stuck like a fly in a bottle, unable to make progress.

In this sense, human progress can be represented by a logistic curve. The first few discoveries are slow and happen almost by chance. Over time, we are able to connect the dots, and eventually, one discovery leads to many others. During this phase, the curve of progress resembles an exponential function, but eventually the rate falls, either because we run out of things to discover, or because we are incapable of discovering the ones left. A common metaphor for this is the “low-hanging fruit” one: we picked up knowledge like fruit from a tree, starting with the closest ones, and each subsequent “forbidden fruit” became more difficult to pick until the remaining ones fell out of reach.

This perspective is not new; many people have said and believed that there is nothing left to discover. For example, Kant famously said that logic had made no progress from the time of Aristotle until his own era (see Russell 2010: 463). The Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce even wrote in 1922 (!) that physics had regressed since the time of Faraday, and that the mathematisation of the subject was destined to be short-lived (Croce 1922: §1). Of course the fact they were wrong does not mean that they will always be, so the question still remains relevant: are we running out of things to discover?

Mathematics Again

The case of Cantor’s theorem that we presented earlier is quite emblematic. Raymond Queneau, who was interested in mathematics, asked the same question: how is it possible that a theorem which took months to prove the first time became a textbook exercise in just a few decades? Queneau’s answer is that over time, the proof becomes simpler, the theorem is incorporated into regular teaching and its simplification makes the theorem easy to use. Finally, if the theorem is not fundamental or “relevant” to contemporary trends, it falls to the rank of exercise in the developments that follow.” (Queneau 1965: 16-17).

This answer seems reasonable at first glance, but does not stand up to further scrutiny. How do proofs get simplified? We usually say that something is simplified if the details are missing, but this is not the case here. The exercise does not ask students to produce an inadequate proof of the theorem or to prove something easier. Rather, the proof has become objectively easier to find and, consequently, easier to understand. But how can this happen?

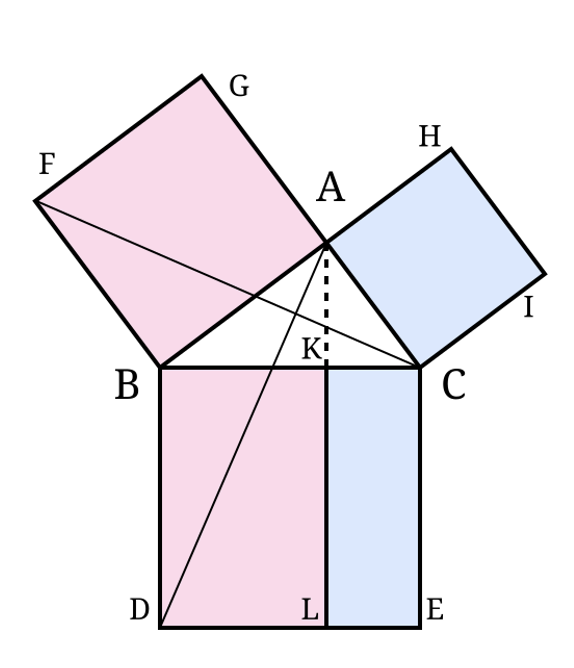

Let’s consider an example with which most people will be familiar: the Pythagorean Theorem. For every right-angled triangle, the area of the squares built on the two shorter sides is equal to the area of the square built on the hypotenuse. Euclid’s original proof is complicated, involving a series of steps to show that the area of square BAGF is equal to the area of square BDLK, and that the area of square ACIH is equal to the area of square CELK. This involves proving other properties about different shapes and constructions within the diagram on the right. The proof of Euclid can be simplified in some ways. But not by much. This is if we follow the same methods: showing that two segments are of equal length just by the parallel postulate and building rectangles are built inside them to show that two areas are equal. The proof is difficult to grasp, and it takes time to master the method in a way that allows it to be used in other contexts.

Now let’s see how we could prove the same theorem today. First, we will consider the sides rather than the vertices, so AB is a, AC is b, and BC is c. We will still use the point K so that c is divided into two segments: x, or KB, and y, or KC. Since the angular sum is constant, we have (x/a)=(a/c) and (y/b)=(b/c). Therefore, a²=cx and b²=cy. Thus, a²+b²=c(x+y)=c², or a²+b²=c². This is the proposition we wanted to prove.

How did a complex, lengthy proof become a couple of lines of manipulation that could be asked of a high school student? We did not simplify anything, as Queneau suggested, nor is the proof any less powerful or rigorous than the original (if anything, it is more so). Instead, the secret is that the new proof was carried out using new mathematical instruments. Unlike Euclid, who could only deal with concrete lengths of segments, we have abstract numbers representing those lengths and rules for manipulating them that do not require justification, such as a+b=b+a. The thing itself has not been simplified, nor have we become more intelligent; rather, we have built a machinery made of a series of new concepts that allow us to process the same result in a much easier way.

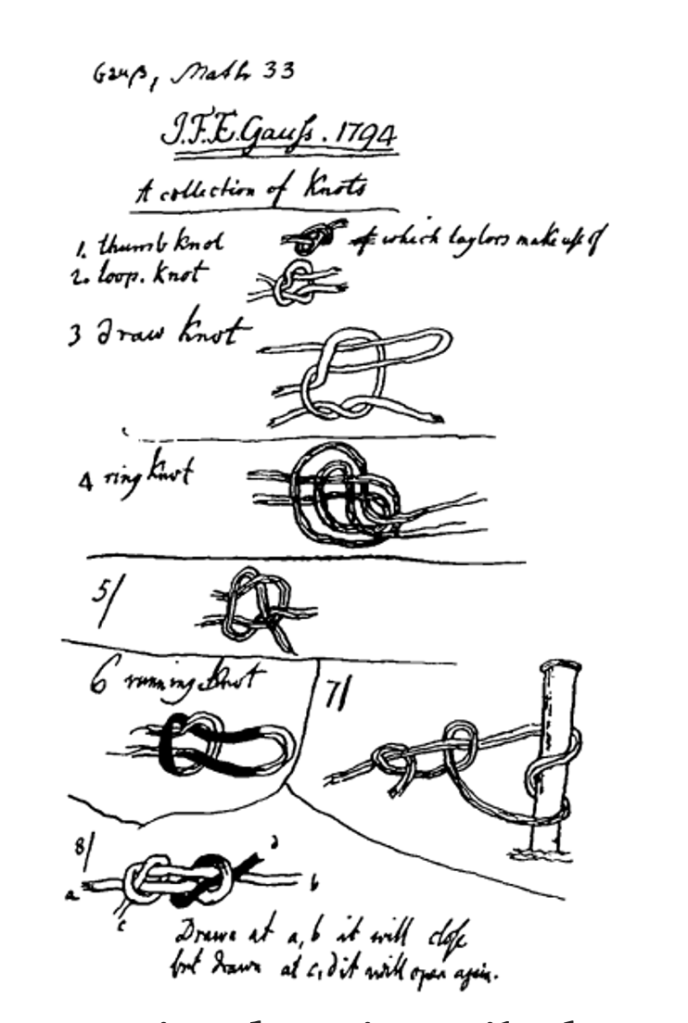

Take for instance the image here on the side, taken from C.F. Gauss’ notebook when he was seventeen (taken from Turner & Griend 1995). It seems that he was attempting to create a catalogue of knots based on an invariant property that he had identified. Nowadays, knots are studied in topology, but in Gauss’s time, they were not considered particularly mathematically interesting, which is a crucial detail. Just as Euclid could only deal with concrete segments, Gauss could only start from concrete knots made of rope and try to derive something from observing them. One might expect a genius to be able to produce something from observation alone, but as far as we know, he did not succeed and did not publish anything about it. This is despite the fact that Gauss was certainly more intelligent than most current master’s students in mathematics, who could easily prove what Gauss thought he saw (and more) using simple algebraic manipulation analogous to that used in arithmetic. What he lacked was not intelligence or perspicacity, but rather conceptual means.

This highlights a characteristic of mathematics that often goes unnoticed, primarily because it can only be observed over a very long period of time: creativity. From Euclid to Cantor, via Gauss, all the cases have shown us that progress in mathematics is not so much about producing proofs and calculations in a computational fashion. What makes the mathematics of our time so much more effective than Euclid’s is the creation of new concepts and abstractions built on top of each other.

On the Reasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics

One could argue that even if we solved the issue of mathematics, we still haven’t defeated the ‘low-hanging fruit’ theory. After all, just because we can create endless, increasingly abstract mathematics does not mean that these creations won’t be limited by the “humanity” they all share. Take physics, for example. Perhaps the endless mathematical creativity of our species doesn’t apply to the external world after all. This view is not unreasonable, but it still relies on the old logistic metaphor of knowledge, and it is not always true that knowledge in physics comes from more complexity.

One thing that usually surprises people when they study the history of physics is Galileo’s experiment on falling bodies. As the story goes, before Galileo proved the contrary, laymen and scholars alike believed that heavier objects fell faster than lighter ones, as it was taught by Aristotle’s and Aristotelian physics. This always results in a bit of shock. Has nobody ever tried to drop two objects from a high place and see what happens? Have all of these people been so firmly rooted in Aristotelianism that they have disregarded what their own eyes are telling them? I always find the stupor for the state of pre-Galilean physics surprising, mainly because it tends to be caused by the same vices it supposedly stigmatises. In fact, by using our own eyes, we could see that by releasing a paper towel and a pen from the same height, the pen falls to the ground way before the paper towel. “This is absurd,” the reader might object, “of course that happens because of accessory causes, like air resistance!” And this is exactly the point! Why do we decide to abstract away air resistance when studying falling bodies? Or resistance in any other medium, for that matter?

As it has been rightly noted (in Rovelli 2015, among others) Aristotle’s theory is very good as long as we maintain that motion happens in a fluid (be it ether, water or air). From Ph. 215A25, He. 311a19-21 and Ph. 215a25 it is pretty clear that Aristotle is suggesting that the velocity of a falling body it is directly proportional on its weight and inversely proportional to the density of the fluid it is immersed in, and directly dependent on its shape. In modern notation v=c(w/ρ), where ρ is the density, w the weight and c the shape constant.

The progress Galileo introduced was of a curious kind: rather than accounting for more phenomena, it was an abstraction that accounted for fewer, namely only motion in a void. Today, considering motion in a void seems natural and obvious. However, this is only the case because we know that most bodies in the universe move in a void, and because we have managed to reduce the motion of celestial bodies and the fall of bodies on Earth to a single cause: gravity. Before that, however, this kind of abstraction was not at all natural; Galilei’s approach was – as noted in Geymonat 1965: 112 – a guess, albeit an educated one, based on the potential he saw in the mathematical methods he could apply to that abstraction.

In this sense, mathematics and the applied sciences are fundamentally different. As we saw with Gauss, we may lack the means to analyse something, but in mathematics, we can simply ignore it and work on something else. This is not the case in the natural sciences. In physics, for example, we always experience nature as it is, already entangled in all its causes and complexities. We can manipulate things as much as we like, but we will never reach a point at which the laws of physics do not act all together at all times. Things are different in mathematics: if I want to imagine a geometry in which Pythagoras’s theorem does not hold, I can carry on as before to see where it leads. Something very similar happened in the history of logic.

The Quest for Truth-Functionality

As we have seen already, the state of logic in the 18th century was rather strange. Kant’s considerations about it were of course incorrect, but not by much. If it is true that many tentative progress were been made since the times of Aristotle, for instance by Peter of Spain, Lambert and others, but everything was still entrenched in the fundamental syllogistic form, so much so that one of Kant’s main pre-critical works, The False Subtlety of the Four Syllogistic Figures, was devoted to reduce those progress to mere insignificant technicalities.

The thing that made the syllogism so useful was its flexibility. No matter what content you put into it, as long as it is in the correct form, things will work out. We could build a syllogism out of modal sentences, like “It is necessary that all humans are mortal,” and sentences with an indifferent amount of syntactic complexity, and it won’t matter; to the extent that the syllogism works, it will do its job. This remained the case for almost two thousand years until an English algebraist named George Boole noticed something interesting. Imagine a universe with only two numbers: 1 and 0. In this universe, all equations would have only two possible solutions: 1 or 0. This is similar to how there are only two types of sentences: true or false. In this context, arithmetic operations seem to behave similarly to logical connectives in natural language. Let’s take multiplication, in the case of a*b, we have that a*b=1 only when both a and b are both equal to 1, just as a conjunction is true only when both conjuncts are true. Similarly, a-1 is like negating a, and a+b is like the disjunction “a or b” which is true if just one of the disjuncts is. Boole was delighted to discover that these definitions could be used to derive the laws of non-contradiction and the excluded middle. Thus, propositional logic was born.

The problem with this kind of system was that, once again, it abstracted many things present in natural language. In Aristotle’s syllogistic, one could derive the proposition “some men are mortal” from the proposition “all men are mortal.” In Boole’s system, this seems difficult to do; the two propositions would be assigned two propositional variables, such as ‘a’ and ‘b’ respectively. While we could still express the fact that b follows from a, as in (a-1*b)-1=1, this relationship is not inherent in the meaning of the proposition, as it was in syllogistics.

In both the cases of Galileo and Boole, we lost the ability to deal with more complex phenomena in exchange for something that was not immediately clear: a way forward and the ability to apply conceptual means more easily than would otherwise have been possible. In short, we have made progress through simplification. The implicit hope in both cases was that we would eventually manage to regain the lost explanatory power in a different way. This hope was fulfilled in both cases: the motion of bodies in fluids can be derived as a special case in Newtonian mechanics, and the expressive power of syllogistics was reinstated and surpassed with the introduction of quantified logic in the late 19th century. While it is possible for human knowledge to become stagnant, we should consider the possibility that it is not complexity that eludes us, but rather simplicity.

Bibliography

Croce, B. 1922. La filosofia di Giambattista Vico, Laterza.

Geymonat, L. 1965. Galileo Galilei, McGraw-Hill.

Turner, J.C. & Griend, P. 1995. The Science and History of Knots, World Scientific.

Queneau, R. 1963. Bourbaki at les mathématiques de demain in Bords, Hermann.

Rovelli, C. 2015. “Aristotle’s Physics: A Physicist’s Look”, Journal of the American Philosophical Association: 23–40.

Russell, B. 1903. Principles of Mathematics, Cambridge University Press.

©️Cesare Cherchi | “Progress Through Simplicity.”, IPM Monthly 4/12 (2025).