What’s Next for the Aristoteles Latinus?

An interview with Lisa Devriese

By Isabel Inzunza Gomez

The Aristoteles Latinus project is a cornerstone in the field of medieval studies, dedicated to the critical edition of all medieval Greek-Latin translations of Aristotle. Overseen by the International Union of Academies, this project plays a pivotal role in understanding the various forms in which Aristotle’s texts were read and utilized in the West during the Middle Ages. The Latin translations of these texts were essential tools for the study of science and philosophy, forming the canonized foundation upon which all commentary on Aristotle’s work was based.

About Lisa Devriese

Since 2020, the Aristoteles Latinus project has been under the new direction of Professor Lisa Devriese. An assistant professor at the De Wulf-Mansion Centre, Prof. Devriese is also the Secretary-General of the Société Internationale pour l’Etude de la Philosophie Médiévale (SIEPM). She earned her doctoral degree in 2018 at KU Leuven with a dissertation focused on the reception history of pseudo-Aristotle’s Physiognomonica in the Middle Ages, a text she has since edited for the Aristoteles Latinus series. Currently, she is about to publish a critical edition of the medieval Latin translation of pseudo-Aristotle’s De coloribus. Her scholarly pursuits are deeply rooted in the reception of Aristotle’s philosophy, the editing of medieval Latin texts, and the exploration of marginal annotations in manuscripts.

Interview

Isabel Inzunza Gomez: The evolution of technology sure opens some exciting possibilities within digital humanities that could significantly impact the Aristoteles Latinus project. As its director, could you outline your vision for the project’s future and explain how you plan to weave these contemporary methods into its longstanding legacy?

Lisa Devriese: Absolutely. First and foremost, we aim to complete the editions, a commitment made back in the 1930s with a 100-year timeline. As we approach that mark, it’s clear we have a substantial amount of work left. We are only halfway! Our immediate challenge is securing new editors and funding, as both are crucial for progressing with the longer texts that require decades of dedicated work—a daunting commitment in today’s fast-paced academic environment. My role as director isn’t just about steering the project in a new direction but revitalizing interest and demonstrating that the project is very much alive. We’ve increased our outreach, including organizing conferences to mark significant anniversaries and engaging with media. It’s vital to convey that critical editions are fundamental to the study of medieval philosophy—they’re the very foundation on which scholarship is built. Without them, there’s a significant gap in our understanding and ability to study these philosophical works.

IIG: Considering the project was initially expected to be completed within 100 years and you’re now saying we’re only a bit more than halfway through, do you see the potential for accelerated progress with the advanced tools and international team you have at your disposal? Could we see completion in, say, the next decade?

LD: Realistically, no, I don’t see us finishing within the next ten years. The texts still awaiting editing are substantial and complex, involving extensive traditions and numerous manuscripts. Editing such texts could take up to 20 years for just one. We have a fantastic team of editors, but each focuses on a different text, so more editors doesn’t necessarily mean faster progress. It’s crucial that we find the right editors for each treatise and secure necessary funding to continue. There are still several critical treatises without dedicated editors, which poses a significant challenge to our timeline.

IIG: Can you discuss the specific challenges involved in creating critical editions of Greek-Latin translations? I assume finding editors proficient in these ancient languages must be quite difficult.

LD: Yes, it’s definitely challenging because proficiency in both Latin and Greek is essential. While many scholars can read Latin, especially in the field of philosophy, editing these texts requires a deep understanding of both languages. The complexity increases because we no longer have the original Greek texts that the medieval translators used; we only have later versions. So, editors must work with what essentially are interpretations of interpretations, which adds layers to the complexity. For our project, we focus on Greek-Latin translations, though there are also texts that involve Greek, Arabic, and Latin. Each additional language increases the complexity of the editorial task.

IIG: Does technology simplify the process of creating critical editions, particularly with handling such large volumes of manuscripts?

LD: It’s complicated. Over the past few years, I’ve experimented with various digital humanities tools designed to assist with manuscript management. For instance, some tools are meant to analyze manuscript relationships by creating a dependency tree after data is inputted. However, these tools typically handle only about 10 to 15 manuscripts, while we often deal with hundreds. This makes them inadequate for our project’s scale. There are also transcription aids that supposedly help decipher manuscripts by automating the transcription of text from scanned images. While useful for projects with a single large manuscript, our work involves too many manuscripts for these tools to be effective. They often miss nuances such as scribe corrections or differences in ink, which are crucial for understanding manuscript transmission. So far, the technology hasn’t been as helpful as hoped, primarily due to these limitations and inaccuracies. For now, the human eye remains more reliable for our meticulous work.

IIG: So, technology hasn’t reached a point where it could automate your job?

LD: Not yet, and honestly, I hope it stays that way for a while. While AI and technology are rapidly advancing, they still fall short of the nuanced understanding required to handle complex manuscript work. We’ll always need to oversee and interpret what these tools produce. For now, the benefits don’t outweigh the challenges they present.

IIG: Digital editions can reach a global audience more effectively than traditional print. As you plan to publish both digital and print versions of new critical editions, do you believe this approach will significantly affect the dissemination and engagement with medieval and ancient philosophy texts?

LD: Absolutely, digital dissemination broadens accessibility immensely, placing these tools right on users’ computers. However, there are still some gaps in what’s available digitally. For example, while the main text of our editions is online, critical apparatuses and detailed introductions that explain manuscript traditions and textual nuances aren’t included yet. Similarly, the extensive glossaries that we compile for each edition, translating terms between Greek and Latin, aren’t in the digital versions either. These elements are crucial for deep scholarly work, so their absence online means that for comprehensive research, scholars still need to refer to the printed editions. We’re working on incorporating these components into the digital versions, which will enhance their utility for research. But, there’s a balance to be struck between embracing digital innovation and respecting the traditions of textual scholarship. While we move forward, ensuring that our editions are accessible to everyone remains a priority. Currently, there’s a discrepancy where some scholars might cite older manuscripts instead of our edited texts because they’re not fully available online, which is definitely something we aim to correct.

IIG: I noticed that the last update on the Aristoteles Latinus database listed on the website was in 2016. Could there be more recent updates that I might have missed?

LD: Yes, indeed, there has been a recent update, which happened last year. We’ve actually overhauled the database significantly. It’s not just about adding the newly edited texts—though we certainly do that with each update—but we also realized that much of the database’s functionality wasn’t being utilized because it was too complex for users to navigate effectively. As a result, we simplified and enhanced the interface to make it more user-friendly. Now, it’s easier to search for texts, group them, or find specific words and passages. This redesign, completed towards the end of 2022 or early 2023, made the database much more accessible and practical for researchers.

IIG: Can you tell us about any upcoming editions from the Aristoteles Latinus project?

LD: Certainly! I’m actually about to publish my own edition, which should be out by the end of this year or early next year. It’s an edition of Aristotle’s text on colors. It’s a relatively minor work that hasn’t had much attention from medieval commentators or scholars, so while it may not revolutionize the field of philosophy, it’s a necessary addition to our comprehensive collection. Beyond this, I’m starting work on Aristotle’s “Politics,” which is a much more significant text with broader implications for the study of philosophy. The “Politics” is likely to have a much greater impact on the field. There are several other texts currently being edited, and we’re waiting on funding approvals for some major texts, which will determine our future projects. So, while the text on colors is more of a modest contribution, upcoming works like the “Politics” promise to be much more influential.

IIG: The text on colors isn’t expected to revolutionize the field, but does it align more with your personal research interests, or was it a necessary part of the project’s broader scope?

LD: It aligns closely with my personal research interests, actually. My focus has been on pseudo-Aristotelian texts and natural philosophy, which is exactly where this text on colors fits. I was particularly drawn to this edition because we found a unique marginal commentary on it—the only one known from the Middle Ages—right in the margins of the manuscript. This rare find was a significant motivator for me to work on this text. So, while it is true that every text within our project eventually needs to be addressed, my decision to edit this one was driven both by its necessity for the project and my specific academic interests in this lesser-explored area of Aristotelian studies.

IIG: You’ve shared how the marginal annotations caught your interest. How does this fascination shape your direction of the project?

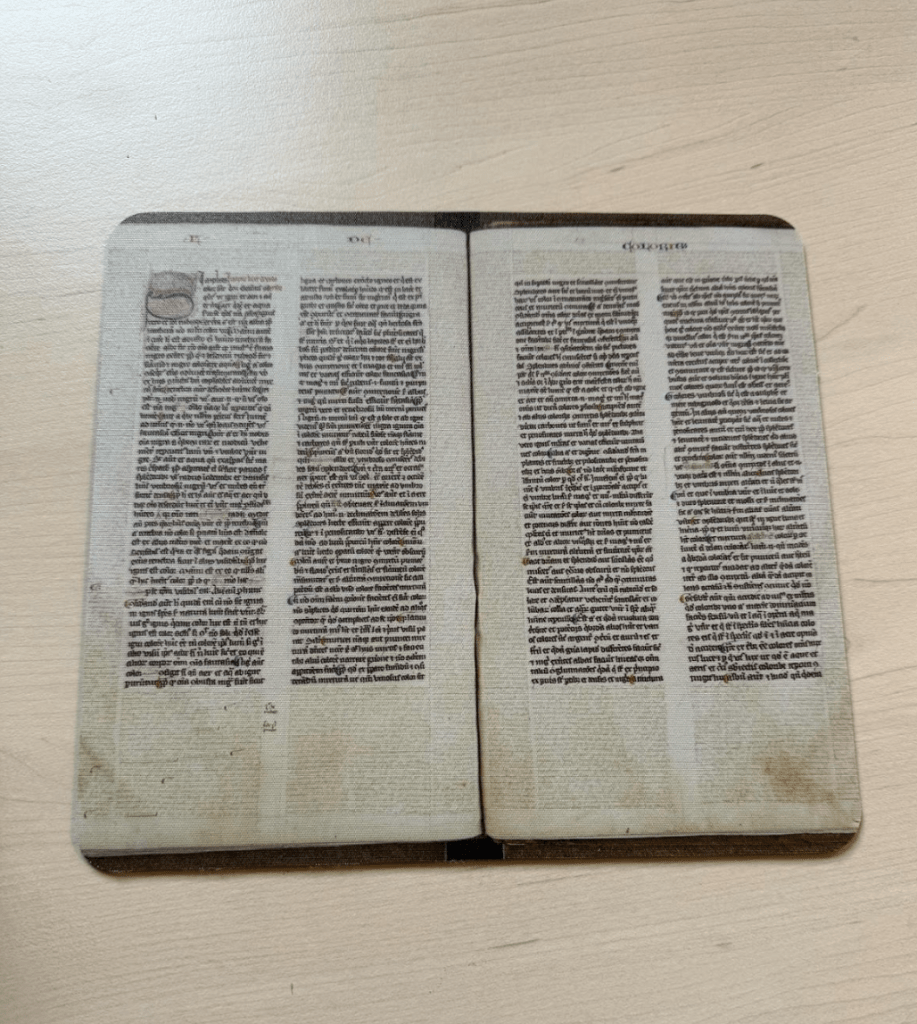

LD: My interest in marginal annotations doesn’t directly influence the overall direction of the project, but it enriches how I engage with the texts I edit. Each editor has the autonomy to delve into different aspects of their texts—beyond just editing. For instance, we are encouraged to explore things like the reception history of the treatises we work on, or how medieval commentators interacted with these texts. My specific focus on marginal annotations allows me to uncover firsthand insights from medieval scholars about the texts—what they found intriguing or how they connected these texts with others. While not every editor may choose to focus on these annotations, I find them a fascinating, though sometimes challenging, source of information. They are often cramped, full of abbreviations, and parts may be cut off, making them tricky to decipher. Yet, they’re immensely valuable. I’ve even gone as far as creating a mousepad printed with the most important manuscript I work on for the Aristoteles Latinus, showcasing all these marginal notes around the main text—it’s a daily reminder of what I love about this work. It might sound nerdy, but it’s a unique way to keep my passion alive and visible in my everyday work environment.

References

Picture 2: https://stories.kuleuven.be/en/stories/aristoteles-latinus-jigsaw-puzzling-for-experts

Lisa Devriese: https://hiw.kuleuven.be/dwmc/people/00099161

Aristoteles Latinus: https://hiw.kuleuven.be/dwmc/research/al

©️Isabel Inzunza Gomez | “What’s Next for the Aristoteles Latinus?”, IPM Monthly 3/5 (2024).