Philosophy, Culture, and AI

An Interview with Martin Puchner

By Sarah Virgi

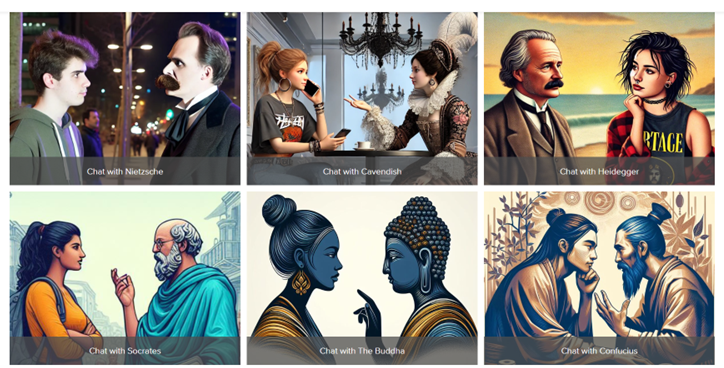

December 2024 – How is artificial intelligence reshaping the way we think, create, and engage with ideas? How will it impact on the way in which we practice philosophy and teach it? For Martin Puchner, exploring AI and what we can do with it has become a way to ponder these questions. Initially driven by sheer curiosity, he has delved into AI’s philosophical potential, by building custom chatbots that bring historical figures like Socrates and Montaigne into interactive dialogue with modern audiences.

In this interview, he reflects on how AI fits within the history of writing technologies, its ability to process and synthesize humanity’s vast cultural archives, and its philosophical possibilities. From turning AI’s “hallucinations” into tools for creativity to using chatbots in teaching and public engagement, his work illuminates AI’s potential as more than a tool—it’s a partner in rethinking culture and philosophy..

About Martin Puchner

Martin Puchner is Professor of Drama and of English and Comparative Literature at Harvard University, and a literary critic and philosopher. He is the author of The Drama of Ideas (2010), The Written World (2017), and Culture (2023). His more recent work focuses on the role of artificial intelligence in culture, art, and philosophy.

The Interview

Sarah Virgi: As an author, you are known for The Written World (2017) and Culture (2023). More recently, you have been focusing on the question of AI. How did your work on the history of writing and culture influence the way in which you approach AI?

Martin Puchner: What first drew me to experiment with AI, when it became available in 2022, was simple curiosity: suddenly there was this thing that could write. Amazing. As someone who studies literature, I couldn’t resist exploring it, testing its abilities and limitations. And when it became possible, in January 2022, to customize GPTs on OpenAI, I reacted in the same way and started to play around with this new writing and thinking technology. It was this curiosity, not my studies in the history of writing and culture, that came first. It was only after I had gotten more of a feel for generative AI that I started thinking about it historically, how it fits in the history of writing technologies that I described in The Written World. From this perspective, AI is clearly an extension of a bundle of technologies associated with writing. In particular, AI provides a new type of access to all the written documents we humans have accumulated since the invention of writing five thousand years ago, an incredibly effective tool for finding, processing, and synthesizing vast amounts of information.

When I wrote Culture, I thought of it primarily as an intervention in the debate about cultural appropriation. But surprisingly, the picture I formed of culture as a vast recycling machine turned out to be perfect for AI, which essentially creates enormous mashups. So, in retrospect, these two books really prepared me for AI, so to speak, and I am sure subliminally nudged me to explore it. But as far as I am aware, sheer curiosity came first.

SV: Recently, you gave a talk in which you claimed that AI can be used as a tool to philosophize. How do you imagine a philosophy that is aided by AI tools? To what extent will this be different from the way in which we practiced philosophy until now?

MP: Actually, I think having a conversation with one of my philosophical chatbots isn’t so different from how we have practiced philosophy all along. This was another other thing that happened when I started working with customized chatbots: I remembered another book project, on the history of the philosophical dialogue. Or rather, to be perfectly honest, I didn’t even remember this myself. I was having dinner with a colleague, the legal scholar Noah Feldman, we were talking about AI, and he suddenly turned to me and said: “didn’t you once write a book about the philosophical dialogue? I think that’s quite relevant for AI since we interact with AI via dialogue?” And suddenly it struck me that he was absolutely right. Why hadn’t I thought of this myself? I don’t know. I think because the term we use for this type of dialogue, “chat,” sounds so slight, even cutesy. But once we ignore that, our interactions with AI can be understood as part of a history of dialogue. In the book (called The Drama of Ideas), I had analyzed how Plato invented philosophy as a form of written dialogue, and later I extended this to other dialogic philosophers such as Confucius and The Buddha. This history is useful for understanding what it means that we interact with AI in the form of a particular type of dialogue. In other words, when I turn Plato’s text into the basis of a Socrates chatbot, I am basically doing what Plato did, just in a slightly different manner, by making it possible for people to engage Socrates in dialogue.

SV: In your work on the history of culture, you argue for the cultural productivity of “mistakes”. One major critique of AI is the large extent of false information that it produces and its lack of transparency concerning its sources. Can you elaborate on where you see the chances, but also the risks of using AI for philosophy and culture?

MP: You’re taking about so-called hallucinations, when generative AI, often in a tone of utmost certainty, makes claims or mentions sources that simply don’t exist. These hallucinations are a good reminder of how generative AI works.They don’t have a concept of reality, of what exists and what doesn’t exist, only of probability. So they make stuff up, stuff that could exist, but doesn’t. All of this is true, but I think the outrage with which these hallucinations are often greeted is largely misplaced. Hallucinations are only a problem if we use AI for factual information. If we do that, we always need to double check. Often it’s enough to ask AI for a source, and it will quickly backtrack and admit when something actually doesn’t exist. But when we use AI for more creative purposes, hallucinations can be great. In a way, they are exactly what Aristotle had in mind when he defined art, in the Poetics, as an art of the probable. So, instead of being outraged by hallucinations, we should welcome them as a unique feature of generative AI which we can use in a variety of ways.

SV: You have also developed custom GPT’s which allow one to converse with important figures in the history of literature and philosophy. What motivated you to develop these tools?

MP: As I mentioned, the motivation was simply curiosity, playing around with a new tool. Then I started to think more systematically about them as part of a history of technology, of culture, and of the history of dialogue. Now, in a kind of third phase, I use them to understand what kind of person or personality a customized AI is. When I customize a GPT to represent, say, Socrates or Margaret Cavendish or Du Bois, I first try to create a distinctive historical person—it’s very much like creating a fictional character. But because these customized GPTs sit on top of OpenAI’s large language model, they have access to all the information used to train that large language model. This means that you can have a conversation with Socrates about the internet, for example by asking Socrates to relate his critique of writing—that it’s unreliable and messes with our minds—to the effects of social media. This, too, isn’t so different from what happens when we read a text: we always bring everything we know to an old text and in this sense make it speak to our present-day concerns. With AI, part of this dynamic process now happens not only in our minds, in the act of reading, but is done by the generative AI agent.

SV: Do you recommend these custom GPT’s to your students and do you use them as tools in your own teaching? If yes, what is your experience from using them?

MP: Yes, I share my GPTs with students as well as with everyone else. A lot of what I do —writing books aimed at a general audience; creating free online courses; editing anthologies of primary texts—aims to make the past accessible. Chatbots do the same. They are lively, interactive ways of engaging sometimes very difficult texts (all my chatbots quote directly from source texts). But to my surprise, a lot of people who are not students have enjoyed them as well. For example, one of by editors, who has been going through a bit of a midlife crisis, reported spending a lot of time with my Montaigne chatbot and said that these conversations have been more helpful than three years of expensive psychotherapy. I also, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, created a chatbot based on Machiavelli and sent it to my university’s president for “leadership advice.” So, you see, there is a chatbot for everyone . . .

©️Sarah Virgi | “Philosophy, Culture, and AI”, IPM Monthly 3/12 (2024).