Paper and Filigree Database: The Corpus Chartarum Italicarum

By Celeste Pedro

Summer 2023 – The Corpus Chartarum Italicarum is an online database of papers produced in Italy since the 13th century, developed by the Central Institute for the Pathology of Archives and Books (Italy). The project was resumed over a decade ago and was recently made available to the public.

Why an online database of papers? Imagine you’re working with a manuscript or a print; the paper that was used to make it can give you clues as to where or when, and sometimes by whom it was created. This information can help identify anonymous works, verify authorship and dates, or better understand trade networks.

A simple analysis might start by checking the presence of watermarks (or filigree), which is very indicative but useless without a database to compare it to. In this case, around 5000 watermarked papers are made available from collections belonging to libraries and archives and privately owned. A substantial part corresponds to an original collection born in the 1930s but lost during the IIWW. It resurfaced in 2003, and efforts to do proper research into these materials began. The collection was enlarged through the years, now including collections from other institutions.

Such is the case with the Corpus Chartarum Fabriano, led by the Fedrigoni Fabriano Foundation and initiated in 2016/17, which accounts for papers produced in Fabriano (Ancona) since the late 13th century, including the collection of papers and filigree set up by Augusto Zonghi in the 19th-century (“Segni delle Antiche Cartiere Fabrianesi”), the first to be made available online.

Setting up a database like the CCI (Corpus Chartarum Italicarum) requires many steps and resources. First comes the conservation of materials, defining scope and methods for data collection, and process protocols, including measurement and digitisation, software (sometimes customised) and guidelines for creating metadata, not to mention the research on historical identification, the creation of controlled vocabulary, or the training of staff. The result is part of what makes a database useful and culturally significant: a thorough standardised presentation and disclosure of information that the public can use.

In an article for the journal TECA (https://teca.unibo.it/), Giovanni Luzi (2022) presents a case study (https://teca.unibo.it/article/view/16010/15303) for which the Corpus Chartarum Fabriano was determinant: the main question was how far (commercial roots, Italian and foreign centres) did the papers produced in Fabriani go from the 13th century onwards?

In 2021, Dante’s Commedia was used to trace which (if any) editions were produced with paper(s) represented in the collection, concluding that the paper from Fabriani had a role in the diffusion of Dante from the start. Manuscript Plut. 40.22 (Medicea Laurenziana di Firenze), for example, contains watermarks that precisely correspond to a dated sample of the mid-14th century. Other manuscripts and prints revealed more details: “La prima edizione a stampa della Divina Commedia vide la luce a Foligno l’11 aprile 1472 per opera del tipografo tedesco Johannes Numeister, che per procurarsi la carta necessaria a stampare le circa 300 copie previste ricorse anche alle cartiere della vicina Fabriano.”

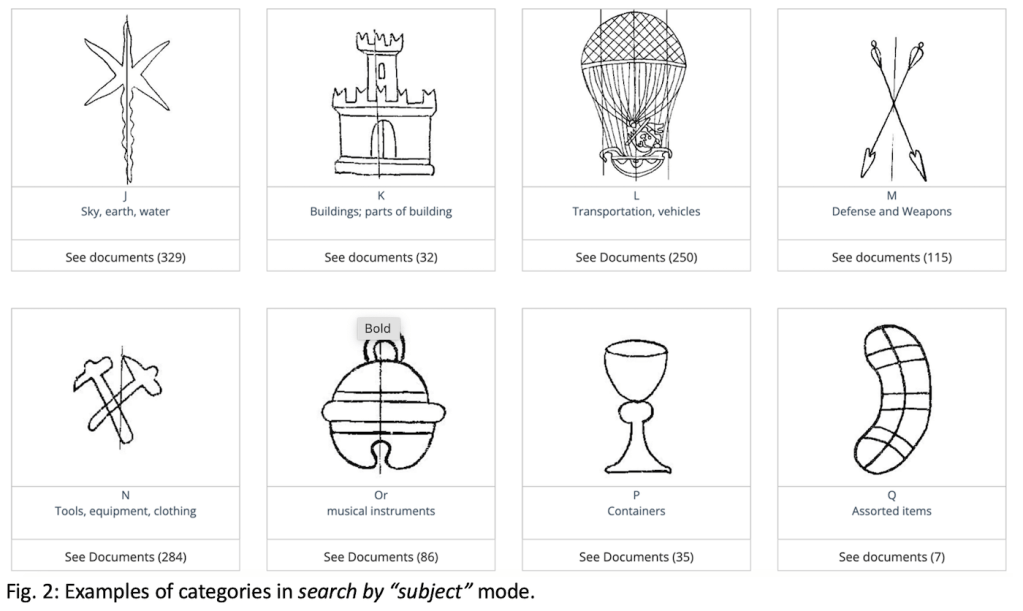

The CCI database can be used with the standard word-based filtering system or advanced search, but the most intuitive search category is the “subject”. If one wants to find information regarding a watermark of which one knows nothing, finding similar drawings (ahead of place or date, for example) is the first logical step. This quick search lets you locate watermarks by keywords and “typical shapes”.

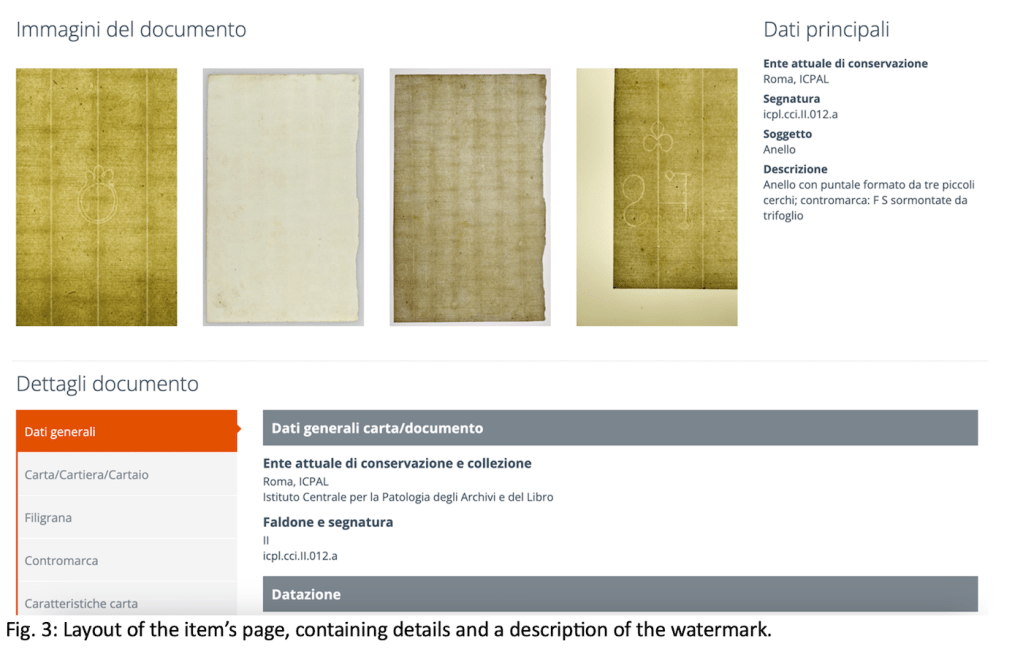

By selecting a sample from a class or sub-classes (example: class A > sub-class1 Man/Man(religion)/Man(rank/politics)/Parts of the human body > sub-class2 Hand/Head/Heart), we get to the item’s page. The information is structured into sections, covering bibliographical information, paper features and watermark descriptions like filigree orientation on the sheet, dimensions, density of wire rods, paper thickness, manufacturing details, typology of the watermark, textual transcription, if that’s the case (single letters, joined or monograms, names or words, numbers, date), date (century and year), internal and external relationships to other samples, and more.

Having this encompassing information on paper characteristics, its production and circulation makes it easier for researchers to trace geographical and economic relationships involving the book business (but also other materials, such as letters) and seller/client dynamics. If papers produced in Italy aren’t in your “line of needs”, why not surf other paper databases? Here’s a good start: https://www.paperhistory.org/Watermark-databases/