HORIZON: Playing Utopias

By Celeste Pedro

January 2025 – Philosophical games are not easy to find. I have mentioned them here (and here) before. Today, I bring you one that has been released very recently. You might ask what this has to do with the digital humanities, but please indulge with me in the fact that it has been released open-access, in digital form, and that that’s the least of its contribution to knowledge dissemination.

Utopia, by Thomas More (1478-1535), has inspired academics for centuries. It embodies the dream of a perfect community, a state of peace where every human being counts and nature flourishes.

While the concept of a perfect community is reshaped as societies progress through problems specific to each generation, the dream remains. The idea that it is possible to achieve a utopian city drives much scientific research. The idea that people can find a way to get along drives all of us; it always has.

One of the reasons, in my view, for not easily achieving “utopia” is that it is terribly hard to resolve terribly complex problems, and we are – generically speaking – not equipped or qualified to do most of the resolving.

Here, of course, comes experience in the form of knowledge exchange. Those who know how to deal with complexity can and should help others do it. The project I present today is aiming precisely at that; they believe “playing a utopian game can make us return to the real world equipped to look for solutions to real problems” and help us develop “utopian thinking”.

Meet HORIZON: A Collaborative Utopia-Building Game

Horizon was developed at CETAPS, the Centre for English, Translation, and Anglo-Portuguese Studies of the University of Porto, where a group of researchers (CETAPS Digital Lab & JRAAS Team) in the field of Utopian Studies got together with game designers to make this idea come true.

It was inspired by other collaborative world building games, such as Beak, Feather and Bone.

The game’s dynamics

Social engineering defines Utopia; roles and functions are well-defined, but it all seems distant to most of us, e.g., a more egalitarian society that lives well with slavery or the fact that private property does not exist in Utopia…

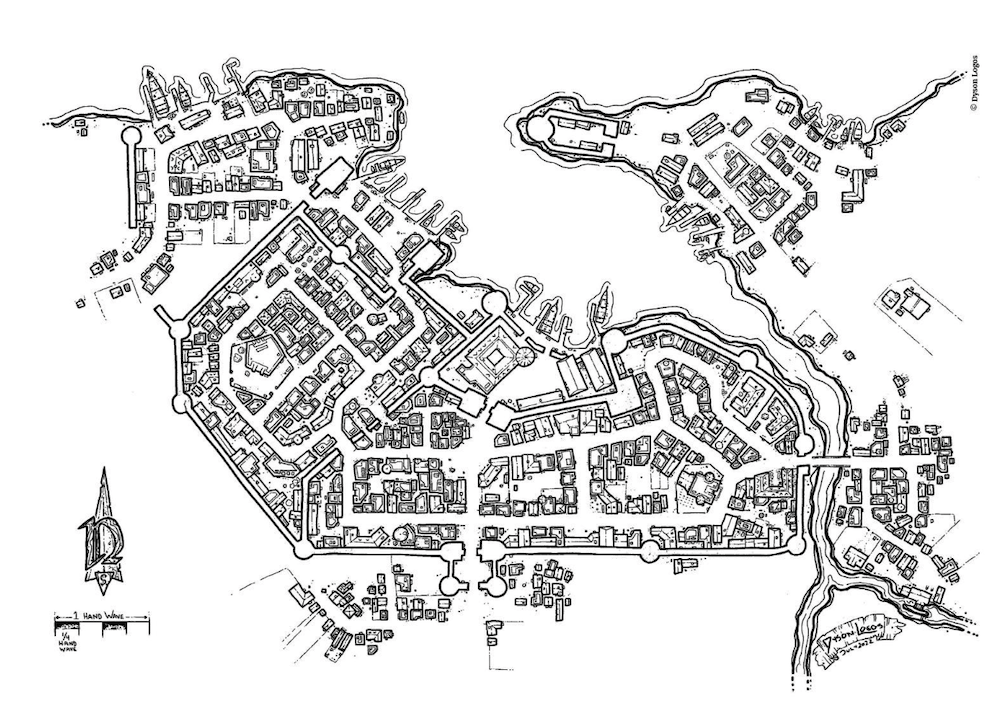

In this game, players can build a map of a utopian territory. They cannot do it alone, though. This is a communal game; utopias are built out of collaborative efforts. Of course, collaboration doesn’t eliminate discord, and that’s where this game starts getting interesting. There are always compromises to be made, the tradeoffs. Players are led to consider the consequences of each move/decision within a social structure.

The game involves determining the values that drive the structure, such as sustainability. Then, the narrative can start. How it will develop and how it will end up looking is to be determined by players at each round.

The cards

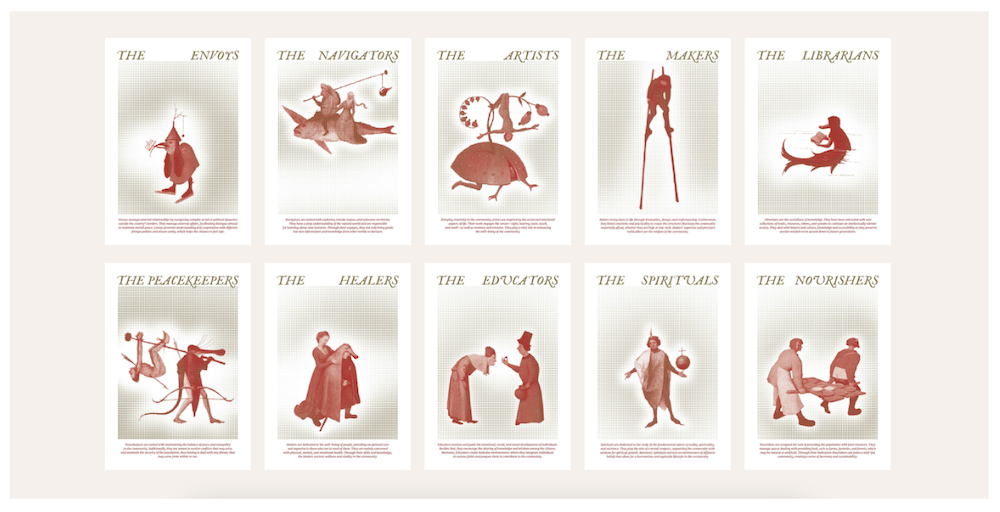

There are 10 cards (the game can have a max. of 10 players), one for each of the Utopian roles (the Envoys, the Navigators, the Artists, the Makers, the Librarians, the Peacekeepers, the Healers, the Educators, the Spirituals and the Nourishers); they represent core occupations or essential functions within Horizon. Each player is assigned a card/role, or, if agreed between players, the roles can change as the game progresses.

The characters

Players are invited to briefly write down what they think a utopian community is and imagine their character – like in a role-playing game, one that reflects their card/role. Then, players start mapping out the places on the map they want to claim and describing those locations. For that, a randomly attributed value is assigned to each location; these values (community, sustainability, equity and openness) will drive the aims of this community and help make decisions.

The maps

If a player is assigned a “Nourisher” card and the value of “Equity”, he will decide a place on the map to build something, like a farm for example, and describe it physically, its purpose and the tradeoffs that need consideration, within this concept of equity, while assuming their role: “Nourishers are assigned the task of providing the population with food resources. Through their dedication Nourishers can foster a well-fed community, creating a sense of harmony and sustainability.”

In the second phase of the game, after all players are assigned a role and places are assigned values, players vote to choose the type of ruler (value and role) and government for their community. Then, players take turns “visiting” the places marked on the map and developing stories based on encounters between characters and situations, thus exploring possible implications of the functions and locations of places within the larger structure and the role each player can perform in resolving issues: “As you explore and build your utopia, you’ll encounter other players’ creations – some may align with your utopian vision, while others may not. You will need to find ways to engage with or adapt to other’s creations – even when they challenge your ideals.”

In the last phase of the game, once the community is taking shape and players have a structured idea of what a utopian community should be, players must ask and answer a few questions to assess how mature their vision is. Issues like gender healthcare or housing for all, war…, will test your ability to critically analyse how things are and how they should be and confront you with preconceptions about roles and values in an open discussion scenario.

How closely related are social structures and spatial structures? What happens at the boundaries of our space, in the various spaces of contact? Can we change a community by changing its structures, physically and/or mentally? These are the questions that start popping into my mind.

Horizon makes us engage in discussions that need to be in place in order to consider better futures for our communities and our roles in getting there. It makes us consider our experience and the experience of others as part of a larger structure that shapes how communities thrive or perish. It also hints towards the need to imagine and dream the place we want to live in before we act.

Fátima Vieira, the Vice-rector for Culture at the University of Porto, summarizes the goals of the project with a call out: “Anyone who plays Horizon will certainly understand that we are formulating the questions the wrong way: more than asking ourselves about the professions we will need in the future, we should ask ourselves what roles we are preparing our young people for, in our schools, in our universities. That is the essential question.”

©️Celeste Pedro | “HORIZON”, IPM Monthly 4/1 (2025).